It seems in recent times, more and more companies are conducting usability testing with an inclusive perspective.

While it's great to see inclusive design become more common, it often seems like the philosophy isn't completely embraced. This seems particularly true when designing for people with disabilities. More often than not, only a handful of participants with disabilities are included in user research and usability testing. This doesn't truly represent diversity and doesn't align with what is considered best practice.

Inclusive usability testing webinar

View the video of Inclusive Usability Testing with Ben Gilmore - our free lunchtime webinar held on August 12, 2021.

Ben chats about why inclusive design is important, how usability testing adds best practice guidelines that go beyond WCAG, and why our aim should be to produce an easy and pleasurable web experience for everyone to use.

Why inclusive design is important

When we design inclusively, our aim is not to discriminate against our audiences by race, age, culture, sexuality or disability. Inclusive design is about improving the user experience for the entire audience. One of the cornerstones is through research with a diverse range of participants, including people with disabilities.

1 in 5 people in Australia has some form of disability. That's over 5 million people, or almost the same as the population of Melbourne. With an increasingly ageing population, this number will only grow.

Statistics show that 80% of people won't continue to use a website or app if their experience is bad. For people with a disability, this has an even greater impact. Usability issues mean that someone with a disability might not even be able to complete a task.

In the book Building for everyone by Annie Jean-Baptise, the author discusses the investment return of inclusive design. The estimate of the Market size of disabled customers in the United States is 1 trillion dollars. Beyond ethical and legal considerations, designing inclusively means you will reach a larger number of customers.

Extreme users and the curb cut effect

There is no such thing as an average person, and trying to design for the average can end in mediocrity.

As Todd Rose states in his book The End of average:

"Our modern conception of the average person is not a mathematical truth but a human invention."

By looking at the average, we oversimplify the complexity of the problems we are trying to solve. No one individual will engage with a design the same way, and an often overlooked part of the design process is using "extreme users" in your research.

An extreme user is anyone who poses an extra challenge to design for. For example, people with disabilities encounter many challenges using digital technologies, making them a type of extreme user.

By designing to meet the needs of extreme users, you are improving the experience for everyone. While this might seem counter-intuitive, some leading innovation companies such as IDEO use extreme users as an integral part of their design process.

The benefit of designing for extreme users is often referred to as the curb cutter effect. The slopes on a curb that ensure wheelchair access also benefit people pushing prams and anyone else who might trip over the step.

In the digital world, we might look at the example of fonts and typography. Larger and clearer fonts help people with low vision read on a website and produce a better overall experience. Rather than seeing inclusive design adding constraints, we should look to our extreme users for insights on how to improve holistically.

Accessibility and inclusive design

The WCAG Accessibility guidelines are an international standard. Conforming to these standards will definitely improve digital experiences. However, guidelines can only take you so far if you want to meet the needs of your entire audience.

Consider the impact of something as simple as an expandable section on a webpage. If the user has low vision and using a screen magnifier, they might encounter difficulties. Imagine if the indicator that informs the user that the content can be expanded is positioned far from the text. At high magnification, the user might be unable to tell that the section can be interacted with.

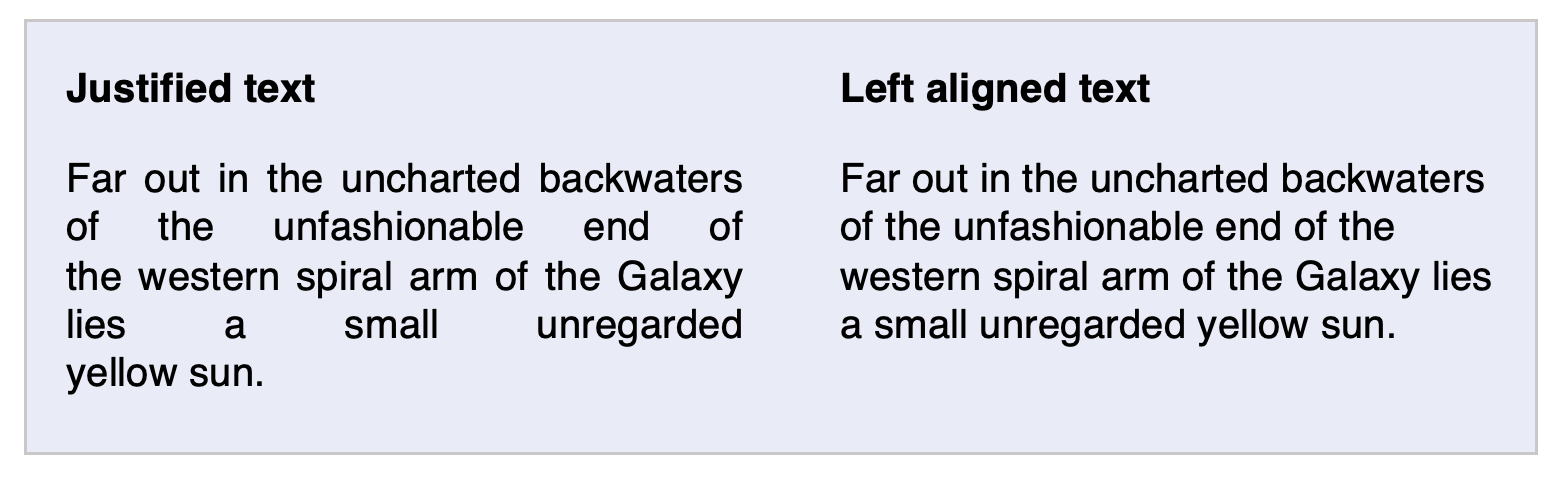

Consider a webpage where text is justified (where the spacing between words and letters are stretched, so both the right and left are aligned). For a person with dyslexia it will be hard to read, the white space and change in spacing between letters will be distracting.

When marked up correctly, these examples would pass the WCAG guidelines. From a usability perspective, they would be sub-optimal.

When we design inclusively, our aim isn't just to make something functional and reliable. It's not enough that someone with a disability can just access information on a website. Our aim should be to produce an experience that is super easy to use and pleasurable for everyone.

This is reflected in the current draft of the WCAG 3 guidelines. In the draft to reach the highest level of conformance, you will need to conduct some form of testing with users. The draft guidelines aren't due to become the standard for a couple of years. When the draft becomes the standard, it will be imperative that you include people with disabilities in your research.

The functional groups

There are six groups of disabilities you need to include in your research.

- Vision – Blindness, colour blindness, low vision

- Hearing - Deafness and hearing loss

- Learning & Cognitive - Dyslexia, Autism, ADHD, and more.

- Physical & motor – Arthritis, MS, Parkinson’s disease and more.

- Speech – Apraxia, Dysarthria, Stuttering and more

- Mental health – Anxiety, Depression, Addiction

There are wide-ranging differences between the disabilities in these groups. It's important to consider this when planning your research.

You also need to consider the different assistive technologies used by your participants. For example, the experience of someone accessing a website with a screen reader will be very different to someone using a screen magnifier.

Someone with arthritis will encounter different issues than someone using switch controls. Likewise, someone with dyslexia will encounter different problems than someone with ADHD.

Test with 3 to 5 users... from each functional group.

Usability testing is a form of qualitative research. Meaning you don't need a statistically accurate number of people to find issues successfully. However just including one of two participants from the functional groups isn't going to be enough. You need to include people across a range of disabilities and assistive technologies.

According to the renowned consultancy The Nielsen Norman group, five participants is the magic number for usability testing. After five participants, 80% of usability issues are typically discovered. Five is also enough to correlate your findings. With over 5 participants, you get an ever-decreasing return on your effort.

Caption: A graph showing the relationship between number of usability testing participants and the percentage of usability problem found. This is displayed as a curve and demonstrates that after 5 to 6 participants there is a decreasing percentage of usability issues found.

Testing with one participant can produce insight, but it can also be misleading. There is a risk of idiosyncratic behaviour or mistakes that aren't representative. It's also highly unlikely you will uncover all the usability issues.

The aim of inclusive usability testing is not to pay lip service to accessibility. You wouldn't test with only one person in a standard round of usability testing, and the same is true when testing to ensure inclusiveness.

For best practice, you should consider 3 to 5 participants from each of the functional groups and assistive technologies used.

Supplement your testing with non-disabled users.

When people with disabilities are included in usability testing, it's often just 4 or 5 participants. It's seen as supplementing or additional to a standard round of usability research. When you consider the benefits of testing with "extreme users" I believe the reverse to be better practice.

People with disabilities will find a larger range of issues, both issues associated with disability and issues that you would find with other users.

For instance, people with dyslexia, motor impairment and screen magnifier users will find the some of the same issues that non-disabled people encounter.

By testing with people with disabilities, you will find a larger range of issues that will benefit the whole of your audience. Testing inclusively and supplementing with non-disabled participants is actually a more effective way of ensuring high usability.

Recommendations

As there are some overlaps when designing for functional groups, you don't always need to test with five participants from each group. An example of this is the tab order of elements on a page. Screen readers and Motor impaired users both use the tab order navigate via the keyboard. By including different types of disabilities in your research, you will strengthen your findings as well as uncover specific issues.

Humans primary sense is vision. So in some ways, you might consider the problems encountered by blind or vision impaired users to be the most extreme. Due to this, you should always test with screen reader users and screen magnifier users.

To be efficient with your user testing, consider if all the tasks you're testing will impact all the functional groups. For example, if what you're testing doesn't have video or audio content, you might not prioritise testing with a person from the deaf community. Ideally, you should be as inclusive as possible, but all projects have a constraint of time and budget.

Our recommendation is to test with 15 participants:

- 4 x Vision - Screen reader users

- 3 x Vision - Screen magnifier user

- 3 x Learning and cognitive

- 3 x Physical & motor

- 2 x Participants with no disabilities

With this combination, you should uncover over 80% of the usability issues that will impact your entire audience, including issues that impact individuals with disabilities. The extra participants with no disabilities enables you to get an understand if the issues are specific to the disability or not.

Depending on what you're testing, you should also consider having additional participants:

- 3 x Hearing - Deafness, particularly considering Auslan as a primary language

- 3 x Speech

- 3 x Mental health

If you're concerned with the usability of your website and if people with disabilities can use it successfully, you should definitely conduct inclusive usability testing. Please get in touch if you need any help getting started.