People with disabilities often run into accessibility issues when using everyday systems or services that most people take for granted.

Using a website, travelling to a location, or reading a menu at a restaurant, can pose challenges for many people if an organisation or business doesn't take the needs of people with disabilities into account.

A supposed solution to this issue is to make a complaint. By letting an organisation know via social media, email or in person, surely the issue will be flagged and resolved? Right?

This rarely happens.

Complaints often result in a generic "Thanks, we'll look into it" message and are never resolved.

Complaints falling on deaf ears become exhausting over time, and eventually people with disabilities are discouraged from complaining and their voices stop being heard.

Complaints are an opportunity

Complaints are an opportunity to improve services and resources, making an organisation a more attractive option for people with disabilities.

By hearing out, addressing and reporting back the resolution of accessibility issues to a complainant, the organisation shows that it cares about people with disabilities. This news tends to spread quickly throughout the disabled community.

Addressing an accessibility complaint will not only support the complainant, but also everyone else who encountered the issue, including people who ended up blaming their own assistive technology or were already too exhausted from complaining.

Lawsuits

If complaints are ignored, it can in certain cases, end up becoming a lawsuit. The Sydney Olympic Games (2000), Coles (2013) and the Commonwealth Bank (2018) all had lawsuits against them due to inaccessible websites/collateral/services. This generated a large amount of negative press for those organisations.

Lawsuits are extremely rare in Australia due to how the complaints process works at the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC).

When a complaint occurs, the AHRC will ask for a comment from the organisation. It's then up to the complainant to decide if that comment is satisfactory. An organisation could involve their lawyers regarding a complaint, resulting in a daunting experience for a complainant to deal with alone.

Most complaints that do become accessibility lawsuits are settled out of court. Therefore we've never had a major trial in Australia that addressed the precedent that having an inaccessible website does not meet the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth).

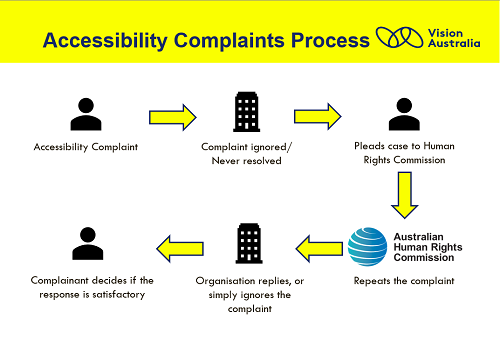

The flowchart below shows generally how complaints tend to happen when the Australian Human Rights Commission is involved.

Long text description of "Accessibility Complaints Process" flowchart:

- A person files an accessibility complaint

- The organisation ignores the complaint and the issue is never resolved.

- The complainant pleads case to the Australian Human Rights Commission

- The Australian Human Rights Commission repeats the complaint to the organisation

- The organisation responds or simply ignores the complaint

- The complainant is left to decide if the response was satisfactory

After receiving the response, the problem is resolved, or the organisation brings in lawyers, or in most cases, nothing happens.

Why complaints often fail to resolve anything

There are simple reasons why complaints tend to fail. One reason is the contact person (usually someone from social media, communications or reception) is simply unaware (usually through no fault of their own) on how to properly handle an accessibility complaint.

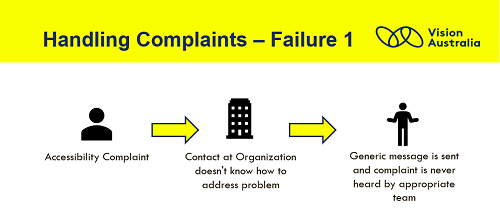

Failure 1 - Unawareness

The first failure is a result of the contact person not knowing who to send the complaint to. Issues such as website accessibility aren't generally well understood by most people and this results in confusion about who is responsible for handling individual complaints.

It's important organisations and business educate their staff about accessibility issues to ensure accessibility complaints are sent to the right team or department. .

For example, website accessibility issues would be sent to a website development or maintenance team, whereas an issue relating to accessible versions of content would be sent to the collateral/marketing teams.

Some organisations will have a dedicated accessibility team, in which case the issue would be sent there.

Long text description of "Handling Complaints – Failure 1" flowchart:

- A person files an accessibility complaint

- The organisation's social media or communications team doesn't know how to address the problem.

- A generic message is sent back to the complainant, and the complaint is never heard by the appropriate team in the organisation.

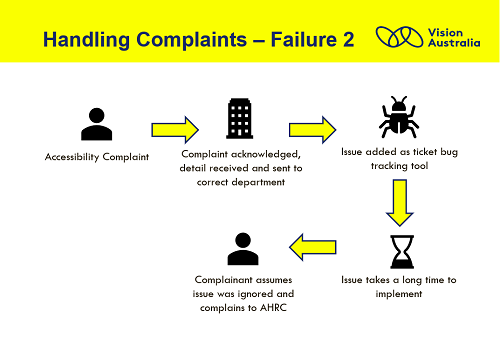

Failure 2 – Lack of communication

The second kind of complaints failure comes from a lack of communication from the team addressing the issue, the contact person, and the complainant themselves. Sometimes an accessibility issue takes time to resolve; systems can be complex and updates can take time to roll out.

During all this hard work to resolve the issue, the person who left the complaint in the first place is often left high and dry with no updates on the issue. To the complainant, this can make it seem like the issue was ignored.

Sometimes, the issue was resolved, but the complainant never heard back and they continue to assume the issue remains.

Long text description of "Handling Complaints – Failure 2" flowchart:

- A person files an accessibility complaint.

- The complaint is acknowledged by the organisation, the detail is received and sent to the correct department.

- The issue is added as a ticket in a bug tracking tool

- The issue ends up taking a long time to implement.

- The complainant assumes the issue was ignored and complains to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

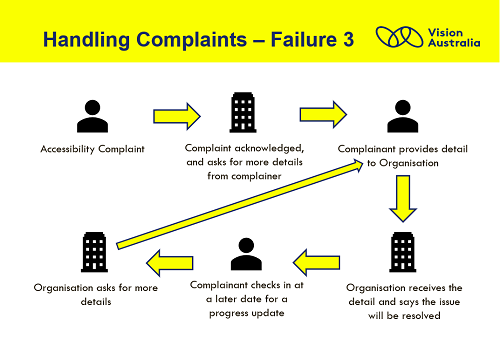

Failure 3 – Running through hoops

The third kind of failure is when the complainant is run through hoops. This is where the organisation makes it seem like something is being done to address the complaint, but nothing is actually happening.

This can be incredibly frustrating for the complainant. This also discourages people from complaining again.

Initially, organisations may go out of their way to have in-person meetings with the complainant, making them feel heard and acknowledged. However, each time the complainant follows up with the issue and they don't receive an answer and are instead asked for more information, leading to an endless loop which can burn out the complainant.

Long text description of "Handling complaints – Failure 3" flowchart:

- A person files an accessibility complaint.

- The complaint is acknowledged by the organisation, and they ask for more detail.

- The Complainant provides more detail to the Organisation

- The Organisation receives the detail and says the issue will be resolved

- The Complainant checks in at a later date for a progress update

- The Organisation again asks for more detail, return to step 3.

How an organisation can ethically resolve complaints

There is a method that organisations successfully use when they receive an accessibility complaint. A communications pathway is established with the complainant, and contact persons know where to direct accessibility related issues. The next step will ensure the remediation of the issue is successful.

User testing with people with disabilities allows confirmation that the inaccessible service or resource is now accessible. The organisation can then go back to the initial complainant and ask if the issue is resolved.

Many complainants often fall into the trap of providing free user testing with the organisation, going back and forth until a solution is reached. Often people with disabilities don't have the time or energy to go through this process for free.

By testing with people with disabilities first and getting the remediation right, there is a much higher chance of getting a positive response from the initial complainant.

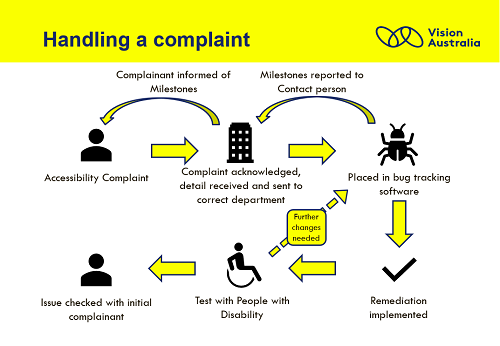

This leaves us with the final flowchart on how to resolve complaints:

Long text description of "Handling a complaint" flowchart:

- A person files an accessibility complaint.

- The complaint is acknowledged by the organisation, the detail is received and sent to the correct department.

- The issue is placed in a bug tracking software.

- As the bug progresses through milestones, this is reported to the contact person, and this information is passed on to the initial complainant.

- The issue ends up in a remediated state.

- The remediation is tested with people with disabilities, if the issue is not yet resolved, the issue will go through a loop of further changes until the people with disabilities can complete the task.

- The initial complainant is informed that the issue was found to be working with other people with disabilities and to ask for a final confirmation from them.

For people with disabilities, it's up to the organisation to decide what to do with the complaint, however, the complaint will gain some additional weight by using a complaint template provided freely by the W3C before contacting the AHRC.

Digital Access at Vision Australia has a range of services, including user testing, to help ensure digital assets, such as websites, documents, ATMs, kiosks and mobile apps are accessible to everyone. We're proud to be the leading provider of accessibility training in Australia, with public and in-house training options for organisations available.